Hidden in Plain Sight

by Axxenne & Camille Circlude of Bye Bye Binary

How does queerness appropriate and create new codes to find living spaces

This essay, written by two members of the collective Bye Bye Binary, Axxenne & Camille Circlude, is written in a common framework of Western-centric graphic references. This system, by its nature, marginalises a great deal of knowledge.

To structure communication is a fundamental characteristic of the human species, even before the appearance of the first writing systems. Indeed, as social animals, human beings need to come together and identify with their communities.

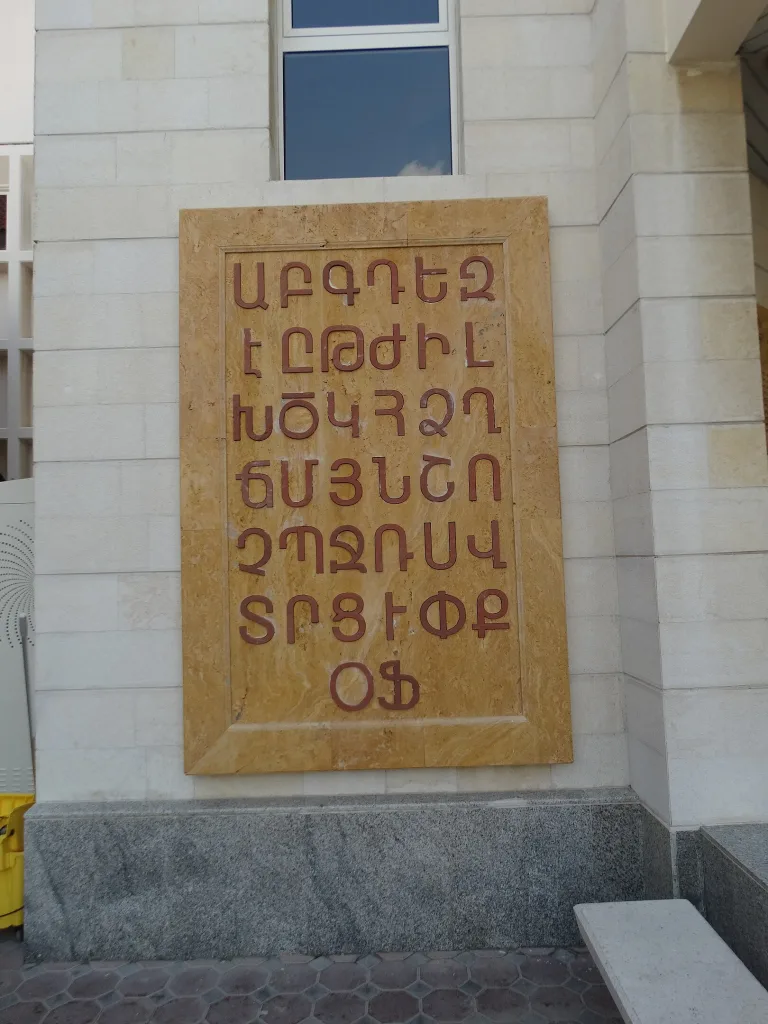

The use of symbols, codes and specific scripts, alongside the capacity to decipher them, enhances a sense of belonging within a community, society, micro-society, or network. While these graphic signs facilitate communication for a greater number of people, they also facilitate secrecy, which can serve to protect oneself from systems of authority or grant certain privileges among one another.

The case of Freemasonry provides a clear illustration of this point. This initiatory and philosophical society has disseminated symbols, signs, and codes across the globe. The square and compass are among their most widely recognised symbols.

Religions also have a wealth of symbols, sacred icons, and objects of worship. By undergoing initiation and apprenticeship, individuals can gain an understanding of these symbols, icons and objects, enabling them to become part of the community. In doing so they develop a common language, line of thought, and culture.

When employed by the dominant majority, codes and symbols serve to gain and maintain privileges. In contrast, the use of codes by marginalised communities allows them to recognise each other, meet in secret, or escape violence.

In Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg recounts how the lesbian community employed a sound code (stopping the music by pulling the plug on the jukebox) to signal the imminent arrival of the police. Bar raids and police violence against lesbian butches were commonplace at a time when wearing men’s clothing for a person assigned female at birth was still outlawed.

The Hanky Code is a communication system based on the use of the bandana. It has been in circulation among the LGBTQIA+ community —mainly in gay cruising areas — since the 1960s. The colour of the bandana and its position on the right or left of the back pocket of trousers indicate one’s preferences in terms of sexual practices. This allows individuals to identify the likely compatibility without much need for verbal discourse.

“With regard to language, the example of Polari —a mongrel language used in England, mainly London — is particularly representative of the links between language and culture. It was spoken almost exclusively by male actors, choristers, showmen, professional wrestlers, sailors and sex workers in the context of the gay subculture. Linguist Paul Baker explains: ‘Polari was much more than a camp fad, however. It was a necessity. In a world where homosexuality was stigmatised through the institutions of law, medicine and religion, these men needed a way to express themselves without getting caught.’”[1] [2]

The use of codes can be ambiguous, with the potential to be used by those in power to identify and mark a section of the population. One notable example is the pink triangle used by the Nazis to persecute homosexuals. The triangle was later recovered, turned inside out and used as a symbol of the struggle waged by Act-Up during the HIV/AIDS crisis. Similarly, the term ‘queer’ has been reappropriated by the LGBTQIA+ community, originally an insult meaning ‘strange, weird’. This process of reappropriation is known as ‘flipping stigma’.

The intention behind the use of graphic codes can be multifaceted and occasionally paradoxical: between the desire to be accessible and understandable to as many people as possible (e.g. the rainbow flag) and/or to remain a marker of recognition for its community without being perceived or read by the uninitiated.

The graphic signs specific to a community can also be stolen by people or institutions who are not involved, who do not belong to the community in question, as a fashion statement or an attempt to recuperate. This is where the risks of pinkwashing, queerwashing and cultural reappropriation arise. The use of symbols of LGBTQIA+ struggles on T-shirts by major ready-to-wear brands is an example of the dilution of their original meaning in the pursuit of economic gain.

To remain elusive, marginalised communities frequently utilise their creativity to adapt their codes once they have been integrated into mainstream environments.[3]

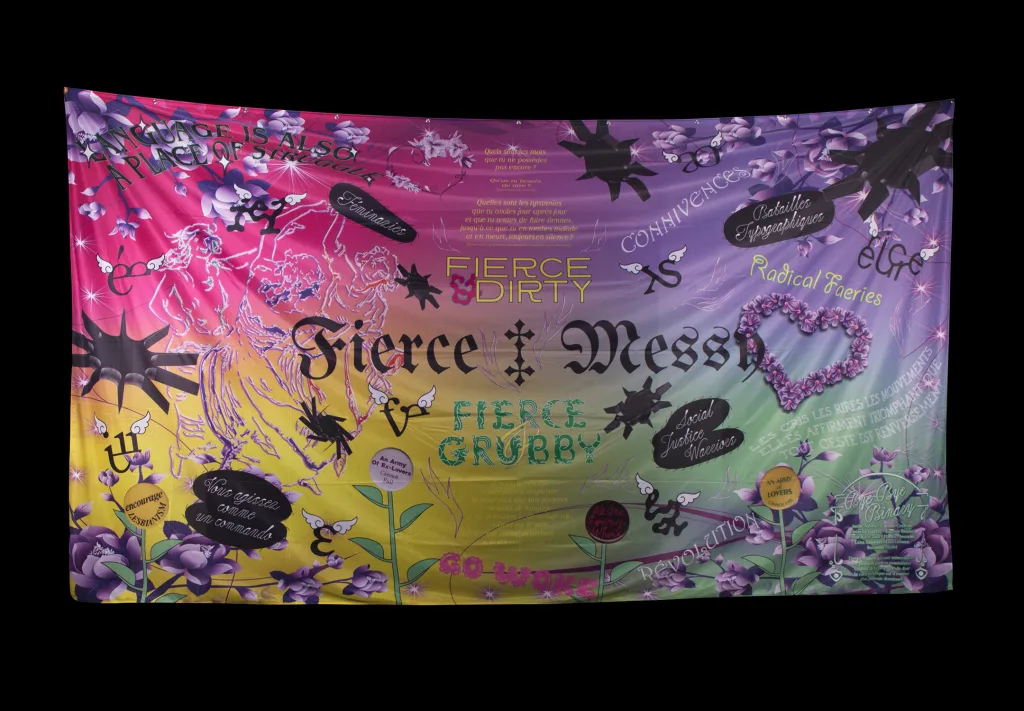

Bye Bye Binary is a Belgian-French collective engaged in the creation of new typographic typefaces. Its members have long advocated for the opening of imaginaries as a means of facilitating people’s reclamation of language and writing codes. They encourage the “choice of the non-choice”[4] to prevent the reproduction of normative spaces.

“The development of new languages based on the values held by marginalised individuals enables the reconstruction of an alternative reality in which it is possible to be represented or simply exist. These mongrel languages are constructed in opposition to the dominant language.”[5]

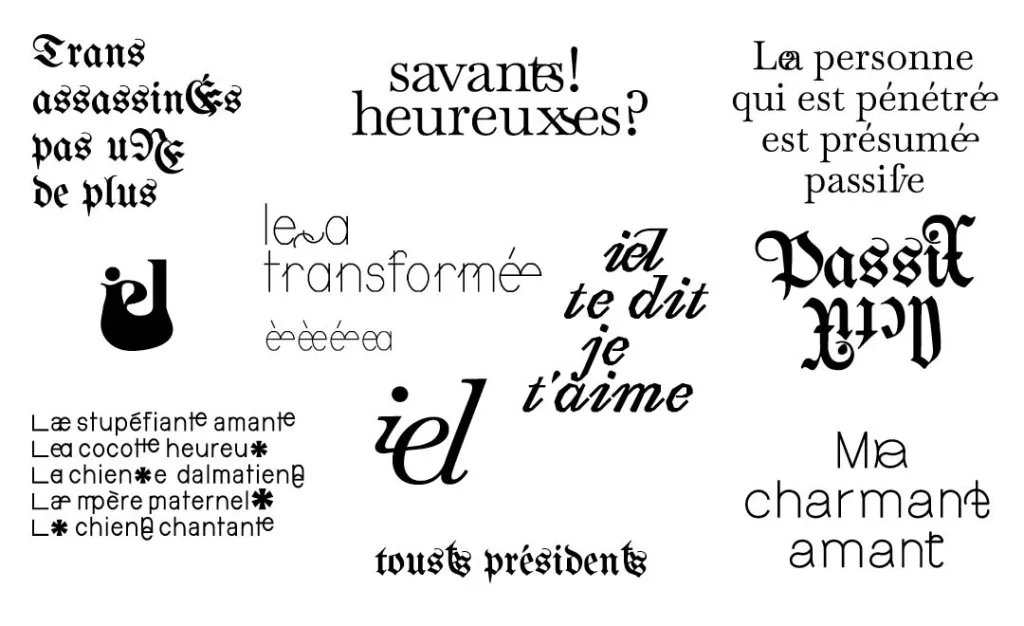

Dealing with the French language from a queer perspective often carries a distinct taste. It frequently concerns gender-specific roles, both in content and form, with an assertive codification of the role that every man and woman must think, do or be. Ultimately, it all comes down to the subject, the “he/she”.

This prompts a series of questions for marginalised people:

- How can I identify with these words, concepts, and ideas?

- How can I be satisfied with the woman who loves the man, the man who protects the woman?

- Are these identities fixed at birth, from which we will never move or question for the rest of our lives?

- Would it be possible, if we were allowed, to exist beyond the margins?

- To go beyond reading between the lines?

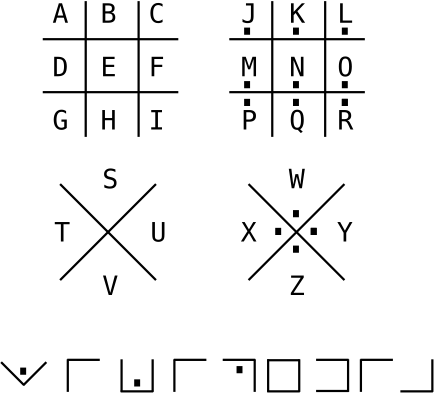

Post-binary typography — which proposes new letterforms to overcome the gender binary present in certain languages, principally French — can be seen as a set of graphic codes creating a sense of identity within the community. Fonts containing these specific ligatures are, in spite of themselves, a marker of recognition.

By incorporating post-binary ligatures into existing fonts (fork), type designers transform them into a “queer” font, breaking down the usual codes of writing.

By creating space for agender, genderfluid, non-binary,, and trans identities within the existing writing system, post-binary typography becomes a tool for reclaiming colonised spaces as a Trojan horse[6].

Visual codes are an essential component of language. Bye Bye Binary regularly employs a specific graphic vocabulary (axes, arm-locks, Molotov cocktails, shurikens, flowers, hearts, emojis, gradients, drop shadows, etc.) in its graphic creations (posters, flags, fanzines, etc.). Some graphic elements are already part of the community’s own language, such as the axe[7] symbol (which can be seen to flip the stigma of the “woodcutter” slur against lesbian butches). Others follow camp[8] and kitsch aesthetics, such as the use of gradients or drop shadows, which are not validated in the field of what is commonly known as “good design”. These graphic objects subsequently serve as codes of recognition that resonate with an entire community.

French post-binary writing is a daily challenge facing the authorities in power. The Académie française (which has no decision-making power in this area) culturally induces codes of “good speech” and “good writing” and slows down the emergence of new, more organic forms of communication.

This arbitrary selection of language use ideologically serves the dominant classes, limiting funding for research and action by language workers. Without funding, there is little chance of existing beyond the margins, little chance of paying the rent, little chance of making this work a daily and secure activity.

The Bye Bye Binary collective is deeply optimistic, believing in free knowledge and tools that can be used by and for everyone, easily deployed and applied by as many people as possible. The use of new codes by communities will go beyond the dusty skeleton of obsolete codes and give rise to new forms. Our codes will no longer be hidden, and others will enrich the sum of our existences. Bye Bye Binary is pleased to be involved in this process and looks forward to witnessing the emergence of these new forms.

[1] Paul Baker, “Polari, a Vibrant Language Born out of Prejudice”, The Guardian, 24 May 2010

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2010/may/24/polari-language-origins

[2] Camille Circlude, La typographie post-binaire. Beyond inclusive writing. Éditions B42, Paris, 2023.

[3] Further reading: Pierre Niedergang, Vers la normativité queer, Editions Blast, Toulouse, 2023.

[4] Camille Circlude, La typographie post-binaire. Beyond inclusive writing. Éditions B42, Paris, 2023.

[5] Camille Circlude, La typographie post-binaire. Beyond inclusive writing. Éditions B42, Paris, 2023.

[6] The Trojan horse metaphor in writing is borrowed from Monique Wittig.

Monique Wittig, “The mark of gender”, The straight mind, Paris, Amsterdam, 2018, p. 122.

[7] Or just because a member of BBB is named “H” (same pronunciation as “axe” in french).

The labrys is a double-headed axe. In Greek and Roman mythology, it is associated with the Amazons, as well as various goddesses such as Laphria, Artemis and Demeter. In the 1970s, lesbians adopted it as a symbol of lesbian feminism.

[8] Further reading: Susan Sontag, “Notes on ‘Camp’”, Partisan review, Fall 1964.